Writing Samples

LOVING RELATIONSHIP WITH DAD

IS NOT ENDED BY HIS DEATH

By Molly Kavanaugh, The Plain Dealer: January 25, 1997 [pdf]

.jpg) A year ago tomorrow I began a journey into a foreign land. At the time I was too full of sadness and busyness to know that my dad's death would take me somewhere new and strange.

A year ago tomorrow I began a journey into a foreign land. At the time I was too full of sadness and busyness to know that my dad's death would take me somewhere new and strange.

Weeks later, in a grief support group, someone labeled it for me: Death ends a life, not a relationship. Makes sense, doesn't it, I told my son, Cody, now 7. I have known my dad all my life, six times longer than I have known my son. Just because my dad is dead doesn't mean he has left my life.

The talking and doing things together had been slowly ending for several years. As my dad's Alzheimer's disease progressed, his words were nonsensical and trips to familiar restaurants ended in anger and frustration. Times together were simply that. I would sometimes lie next to him on the bed and rub his balding head. "I used to put curlers in your hair, when I was little and you had hair," I would remind him.

Of course, he didn't remember I had moved away, much less our silly times together. In many ways the lucid moments were the hardest. "Does the disease make people not want to be around me?" my dad asked one day. Eventually he quit asking. "The ship has sunk but the captain is still out," he said. My son explained it another way. "He's like a storybook with some pages missing."

Eventually chapters started to fall out. He thought I was my mother. We weren't sure who he thought my son was. "But he still loves me," Cody said. We began praying his suffering would end before we would have to move him to a nursing home. Pneumonia finally ravaged his body and he was admitted to a hospice. I never imagined I would be with my father when he died, having always assumed that I would get a phone call after the fact.

My brother and I were at his bedside, standing side by side holding his hands as he sighed once, then again and again. I never knew dying could be so peaceful.

We yelled out names of people who had already died - his parents Alma and Ben, his best friend Muzz. "They're waiting for you. Don't be afraid. We'll miss you."

No more than five minutes and it was over.

As families do, we threw ourselves into making the funeral special. We put together a huge collage of photos, found a musician to sing "An Irish Blessing" and reminisced with old friends about the times when Tommy was at his best.

Before the casket was closed, my brother put in a horse racing program. Betting on horses was a fondness the two of them shared. I added a newspaper article I wrote years ago about a mysterious vagabond woman, one of my dad's favorites.

After that, and for a long time afterward, it was all downhill. I cried a lot, but grief comes out in other ways. Sleepless nights, wanting to just be left alone. "Let's pray that Mom isn't cranky anymore," Cody said one night at dinner prayers.

Gathering memories

I joined a grief support group, coincidentally comprised of almost all adult children who had lost a parent. Together we came up with great ideas for keeping our relationship with our parents alive. Twin daughters said they lit a candle at family gatherings in honor of their mother. Another daughter said she was making a pillow out of her dad's ties.

Someone suggested a memory box. I liked that idea and gathered all of the condolence letters, holy cards and such from the funeral, then added special mementos to it. I have just one letter from my dad. He wrote it the summer before I started college and it was full of love, confidence and encouragement. The faded yellow-lined note went inside. So did one of his favorite caps, his watch, the ID bracelet he wore after his memory left him.

My dad was impossible to shop for, so it was always great success to find something he actually liked and would wear. My mom gave these clothes back to me - a white jacket, a gray sweat shirt, a navy blue polo - and I began wearing them around the house.

One gift I knew my dad would always like was a box of candy from Brummer's in Vermilion. Toward the end he would hide the box so we - or whomever he imagined in the house - wouldn't steal his candy. Eventually he would forget where he hid it. I don't mean to make it sound dismal, it was actually something the rest of us could laugh about. For families dealing with Alzheimer's, you look for such funny moments.

Gifts for others

Why stop buying candy now, I decided. For his 79th birthday I brought a box of candy to the support group. Since then on special occasions I have bought candy to give to others with Alzheimer's, sweet tastes being one of the last senses to go. The last man I visited, just before Christmas, reminded me a lot of my father. I held his hand. It felt a bit familiar.

Like a lot of people, after my dad's death my mom began talking to him, often and about almost everything. After nearly 50 years in the same house, I could understand why she did that. It just didn't work for me.

What did work was kind of a weird thing. I would hold out my hand, cupped as if to hold his hand. I don't know why, but it felt like a natural thing to do. My son has helped a lot, too. One night in his dreams my dad came out of the sky and hugged him. His Alzheimer's was gone, Cody said. Once he said he had seen Grandpa.

"Really?" I said casually.

Well, he continued, he hadn't really seen Grandpa but he felt him. Like when he got dressed, Grandpa was sitting in a chair. I was jealous. Still am, though I am slowly finding my way.

It's amazing what you start to remember. I knew I would never forget all the crazy things my dad did in the end. Talking to pillows. Reading aloud every street sign as we drove. Walking out of the house in the middle of the night.

I was so afraid, though, that I would forget the man who was my biggest fan. If a day or two went by and I had nothing in the newspaper, he would call to find out why. His pride for my work paled after I gave birth to his only grandchild. Then he called to find out why I hadn't brought his grandson by.

He was a simple man, prone to grumpiness but easy to make laugh. In later years when the family gathered for holidays and other special occasions, he would say aloud a personal prayer, mentioning us all by name. By "Amen" he was crying. My teddy bear, I called him.

Thankfully, those happy memories have come back. Tomorrow I will open the memory box with my family and tell them about my new relationship with my dad. Later, alone, I will hold out my cupped hand. I know my dad will probably never squeeze it. But that doesn't mean he isn't near.

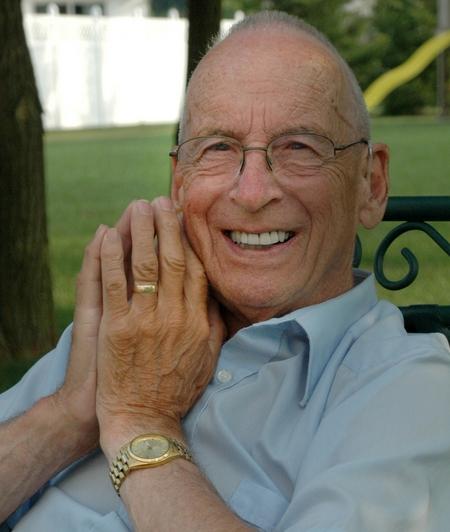

CARL WIEWANDT

May 27, 1923 - Apr. 17, 2013

By Molly Kavanaugh, Port Clinton News Herald: April 18, 2013

Each stroke chipped away at his life, but Carl Wiewandt was a half-glass-full kind of guy.

Unable to drive, talk clearly, or get around without a walker, Carl rarely complained. The 89-year-old Port Clinton man lived at home, where he enjoyed sitting in his comfy recliner watching TV on a big screen and daily visits from his dear friend Norma Smetzer. Meals prepared by Ottawa County Senior Resources and Home Instead aides were tasty, and members of his extended family were always stopping by or calling.

Life was a "thumbs up."

But his optimism was no match for a massive stroke on Easter, and on April 17 Carl died at Stein Hospice Care Center.

Born in Fremont, Carl is a graduate of Fremont High School and Tri-State University in Angola, Indiana. He joined the U.S. Navy during World War II and proudly served our country from 1943-46 in the Panama Canal. Last year he flew to Washington DC on Honor Flight to tour the World War II Memorial, and returned home exhausted and elated.

In 1949, he married Evelyn Cleveland of Clyde, the couple wearing matching tweed suits at their wedding. Carl took a job at Standard Products, and worked there as a chemical engineer until his retirement in 1988.

Though passionate about his political beliefs, Carl's greatest outpouring of expression was directed at his family – including five children, 12 grandchildren, 6 great-grandchildren. He often said he was the luckiest man in the world to have such a crew. "Good genes," he would add, with an elbow jab to the nearest family member.

He took up woodcarving, turning his garage into a wood shop. He carved angels and ducks and figurines and proudly gave them to family and friends.

He never owned a boat, but found plenty of opportunities to go fishing on Lake Erie with friends. His freezer was always stocked with perch and walleye, but as his health declined, the frozen catch dwindled. The last bag of perch was eaten Christmas Eve.

Carl's favorite holiday was May 27, his birthday. In recent years he donned a silly Winnie the Pooh birthday hat with twinkling lights, and happily posed for cameras. He was looking forward to blowing out 90 candles.

He was a member of St. John Lutheran Church in Port Clinton and the Port Clinton Elks.

Carl is preceded in death by his beloved wife Evelyn, parents Paul and Fannie Wiewandt, sister Dorothy Maloy and brother Edward Wiewandt.

He is survived by brother Paul Wiewandt, children Barbara Vance (Raymond), Carol Imes (Charles), Becky Donahue (Patrick), Frank (Molly Kavanaugh) and William (Lisa), grandchildren Ted Vance (Michelle), Heather (Joseph) Knueven, Adam (Carolyn) Vance, Jennifer (Tracey) Coslin, Christopher (Dawn) Imes, Nicole Imes, Bill (Kimberly) Donahue, Sarah Donahue, Ben Donahue, Cody Wiewandt, Jordan Wiewandt, Katy Wiewandt, greatgrandchildren Bailey Donahue, TJ Coslin, Amber Vance, Maya Vance, Jacob Knueven, Nora Vance, and special friend, Norma Smetzer.

Molly Kavanaugh was a reporter for the Cleveland Plain Dealer for more than 15 years. Below is a sample of articles she wrote:

2 SURVIVE 8 HOURS IN LAKE

ORDEAL TESTED COUPLE'S WILL TO SURVIVE

By MOLLY KAVANAUGH

Publication Date: July 15, 1995 - Continue »

OPENING THE DOOR TO THE ANGELS AMONG US

HOSPICE CHAPLAIN HAS FOUND HER LIFE'S CALLING AS A SPIRITUAL GUIDE WHO COMFORTS THOSE APPROACHING THE END OF THEIR TIME ON EARTH

By MOLLY KAVANAUGH

Publication Date: January 29, 1996 - Continue »

A STAFFER TAKES POOR VETS TO WWII MEMORIAL

EX-AIRMAN SEES IT AS MISSION OF MERCY

By MOLLY KAVANAUGH

Publication Date: November 6, 2005 - Continue »

Alex Olejko dies, was Lorain mayor

By MOLLY KAVANAUGH

Publication Date: September 11, 2009 - Continue »

For nearly five years Molly Kavanaugh was editor of Stein Hospice’s newsletter. She wrote profiles about staff members and volunteers, and feature stories highlighting patients, families and Veterans served by Stein Hospice.

To Read “In Touch,” www.steinhospice.org/news-events/in-touch-newsletter/